Heritage Practices, Architecture & Sites

From Arizona to Pakistan

Walpi, First Mesa, Hopi Nation, Arizona, USA has been continuously inhabited for more than 1100 years.

(photo: Justjeffaz, Jeff Brunton, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

The 1972 United Nations Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm, Sweden, was a pivotal moment in human history. It was the first world conference to make the environment a major issue. Afterwards the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) formally recognized our universal desire to create a balance between human interactions (cultural heritage) and the need to preserve our environment (natural heritage). Why? Because our cultural and natural heritages are “what we have done in the past, and what we will pass on to the future.”

UNESCO designates as human cultural heritage “monuments, such as architectural structures, art and science pieces.” And as our natural heritage “formations that are of outstanding universal value from the aesthetic or scientific point of view.”

Pictured above is Walpi in the Hopi Nation, which has the oldest continuously inhabited dwellings in North America. But the heritage architecture shown in the photo and the ancient ritual practices of its inhabitants have not yet been selected by UNESCO.

Please email us a description with a photo of your experience of Heritage Practices, Architecture, and Sites.

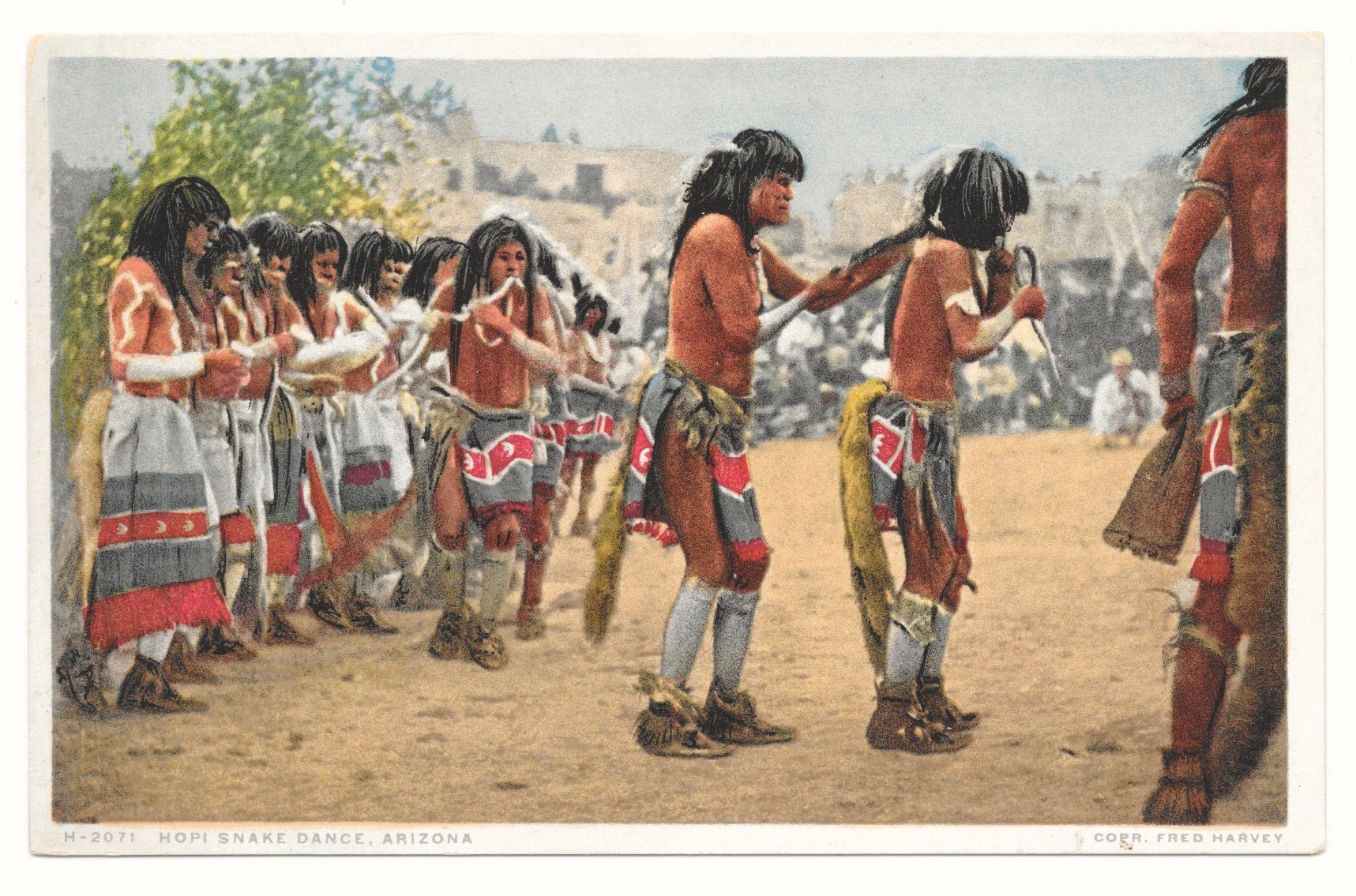

Snake Dancers, Walpi, Hopi Nation, USA – Copyright Library of Congress

Heritage Practices – Snake Dancers

“As a teenager I spent an extended time one summer at Walpi. In late August I attended the annual Hopi ritual of dancing with rattlesnakes. I was working on a near-by ranch owned by a woman who was an honorary member of the Hopi Nation. The matrilineal Hopi invited her to attend their Heritage practice. She brought with her the teenage girls working for her.

What I experienced at Walpi changed my life. We watched young Indians race up the cliff sides, carrying rattlesnakes in their bare hands. Then they danced with the snakes in their mouths, as you see in the 1913 photo above.

Another night in its darkest hours, we were unexpectedly awakened and taken in a pick-up truck to a ritual healing fire in a lonely Hogan, on near-by Navajo land. I still hear the chanted, rhythmic sounds of the medicine man, smell the smoke, and feel the heat of concern rising from closely seated tribal members. I now know I experienced a Navajo Blessing Way Ceremony to restore equilibrium to individual and cosmos alike. I was also experiencing a turning point in my identity.

The Hopi Snake Dance and Navajo Blessing Way Ceremony are both Heritage practices still honored by their respective sovereign nations. To use the words of UNESCO, they are “irreplaceable sources… of life and inspiration… (my) touchstones, (my) points of reference, (my) identity.”

– Jean Gardner, Founder Earth Group Global

Indus River Valley Edutours

Our collaborators at Cube Edutours document, preserve, and share the culture and heritage of the Indus River Valley bioregion. They offer heritage architectural experiences that revive and redefine the Pakistani identity and restore the lost history of the people who passed through and settled in the region over the millennia.

Cube Edutours is developing a platform to compile research and stories, publish and share books, maps, videos, and online content, engage local communities, train guides at heritage sites, organize webinars and conferences, and continue offering onsite experiential learning tours and retreats. They aim to nurture dialog between Pakistan’s provincial archeological departments in connection with relevant groups in other countries.

Cube Edutours recognizes local communities as the earth-custodians of architectural heritage sites, and they support them during visits by paying for traditional storytelling, indigenous food, and local folk music performances. Beyond the visits, they remain connected and assist with fresh water wells, solar power systems, education and health facilities, or other requirements.

For more information see cubeedutours.com.

Permission to use photo from Zain Mustafa

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Indus_Valley_Civilization,_Mature_Phase_(2600-1900_BCE).png

Permission to use photo from Zain Mustafa

Heritage Practices Shape Heritage Objects

Skillful movements of our hands distinguish Heritage practices, like the hand dexterity shown in the photo above of a vase being painted in a workshop in one of the oldest cities in South Asia — Multan, Punjab province in Pakistan.

These hand movements are embodied practices in which our hands know more than we can give words to. Our hands learn these movements not in the conventional in-school method dependent upon our memorizing how-to directions or a theory. Instead, a skilled practitioner demonstrates by showing how their skill is practiced. Then the beginners practice the skill over and over again to learn the hand-arm-whole body movements. They also begin to trust themselves as sources of decision-making when something unexpected happens and they must improvise.

Heritage practices can also be understood from another perspective. They are part of what expert Henry Jenkins calls a participatory culture: “A participatory culture (has) … relatively low barriers to artistic expression and civic engagement, strong support for creating and sharing one’s creations, and some type of informal mentorship whereby the most experienced people pass along what they know to novices.”

Heritage practices are present-day participatory cultural practices as described above. They are not objects for tourist entertainment. Instead, their practitioners hold in their hands a key. Their embodied understanding of caring for and love of their work can release us from our disengaged, distracted modern culture. This present-day, standardized culture has led to the dual crises of the Pandemic and the Climate Emergency.

Heritage practitioners are empowered when we recognize their current relevance. At the same time, their community increases its strength, which can flow exponentially into other groups related to them systemically. Like a pebble tossed into a pool of water, these developments can affect positively our wide-spread longings for a world in which what we do, how we spend our time, matters.

Heritage is our legacy from the past, what we live with today,

and what we pass on to future generations.

Our cultural and natural heritage are both irreplaceable sources of life

and inspiration. They are our touchstones, our points of reference, our identity.